Organisms are continuously changing their position by moving or dispersing their propagules. This ubiquitous feature of life is responsible for generating a wide range of ecological and evolutionary patterns at population margins, including the evolution of increased dispersal rates, the spread of invasive species, and mismatched geographical and niche limits. My research aims to elucidate how dispersal generates these biogeographical patterns across scales in unison with other biological processes.

My research work combines both theoretical and statistical approaches. I use theory to generate empirically testable insights that allow us to unify concepts across seemingly disparate systems that are otherwise challenging. Naturally, my research relies on long walks and pen and paper. Although my research has a strong theoretical bend, I collaborate with empiricists to test theoretical predictions.

Climate Adaptation

As the climate changes, many species are forced to move polewards. However, this poses a risk to species with limited dispersal capacity that are slow to track the climate. Alternatively, a species may adapt to the local climate, which can buffer against species extinction. Therefore, to understand species’ response to climate change, we are building process-based hierarchical Bayesian models to identify the genetic basis of local adaptation. Our statistical method offers two advantages over traditional phenomenological statistical models. First, we provide a rigorous framework to probabilistically estimate genetic variation from noisy and incomplete genetic data, e.g., RAD and low-coverage genome sequencing. Second, we use a demographic evolutionary model to partition the genetic variation into adaptive and non-adaptive components.

For more, see:

Goel, Nikunj, Christen M. Bossu, Justin J. Van Ee, Erika Zavaleta, Kristen C. Ruegg, and Mevin B. Hooten. “Identifying genomic adaptation to local climate using a mechanistic evolutionary model.” bioRxiv (2024)

Biological invasions

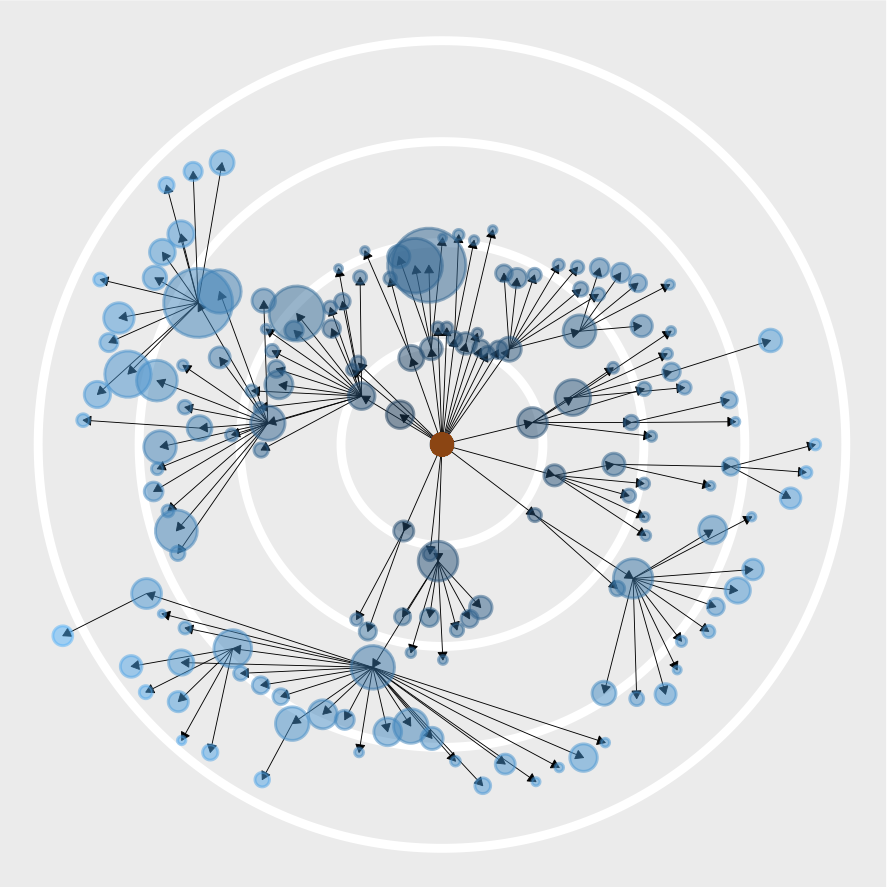

We face an invasion crisis. Rapid globalization of trade and commerce has displaced many species beyond their native realm, resulting in massive monetary and biodiversity losses. Therefore, understanding the drivers of the establishment and spread of invasive species is critical to maintaining ecosystem health.

To this end, I am exploring the interplay between population demography and human transportation networks to study two broad questions: how do species spread via human dispersal pathways, and why do some species become more invasive than others? Understanding these questions will advance ecology theory and yield insights to control invader populations and mitigate their adverse effects.

For more, see:

Goel, Nikunj, Andrew M. Liebhold, Cleo Bertelsmeier, Mevin B. Hooten, Kirill S. Korolev, and Timothy H. Keitt. “A mechanistic statistical approach to infer invasion characteristics of human‐dispersed species with complex life cycle.” Ecological Monographs 95, no. 1 (2025): e70003.

Spatial sorting

Heritable variation in traits that confer differential lifetime reproductive success can fuel evolutionary change by natural selection. However, at margins, populations may be subjected to another kind of selection pressure—traits that confer dispersal advantage may be overrepresented in newly occupied patches even if those traits do not confer a fitness advantage. This mechanism of directional evolutionary change is referred to as spatial sorting. As natural habitats become fragmented and new invaders are introduced, spatial sorting may be a norm than an exception.

Starting from the first principles, I am developing the theory of spatial sorting to answer: How do traits change at the margins? How can we design experiments to measure and interpret trait changes at margins in the broader context of evolutionary theory?

For more, see:

Goel, Nikunj, Mattheau S. Comerford, Anastasia Bernat, Scott P. Egan, Thomas E. Juenger, and Timothy H. Keitt. “Measuring the Strength of Spatial Sorting.” bioRxiv (2025).

Determinants of range limits

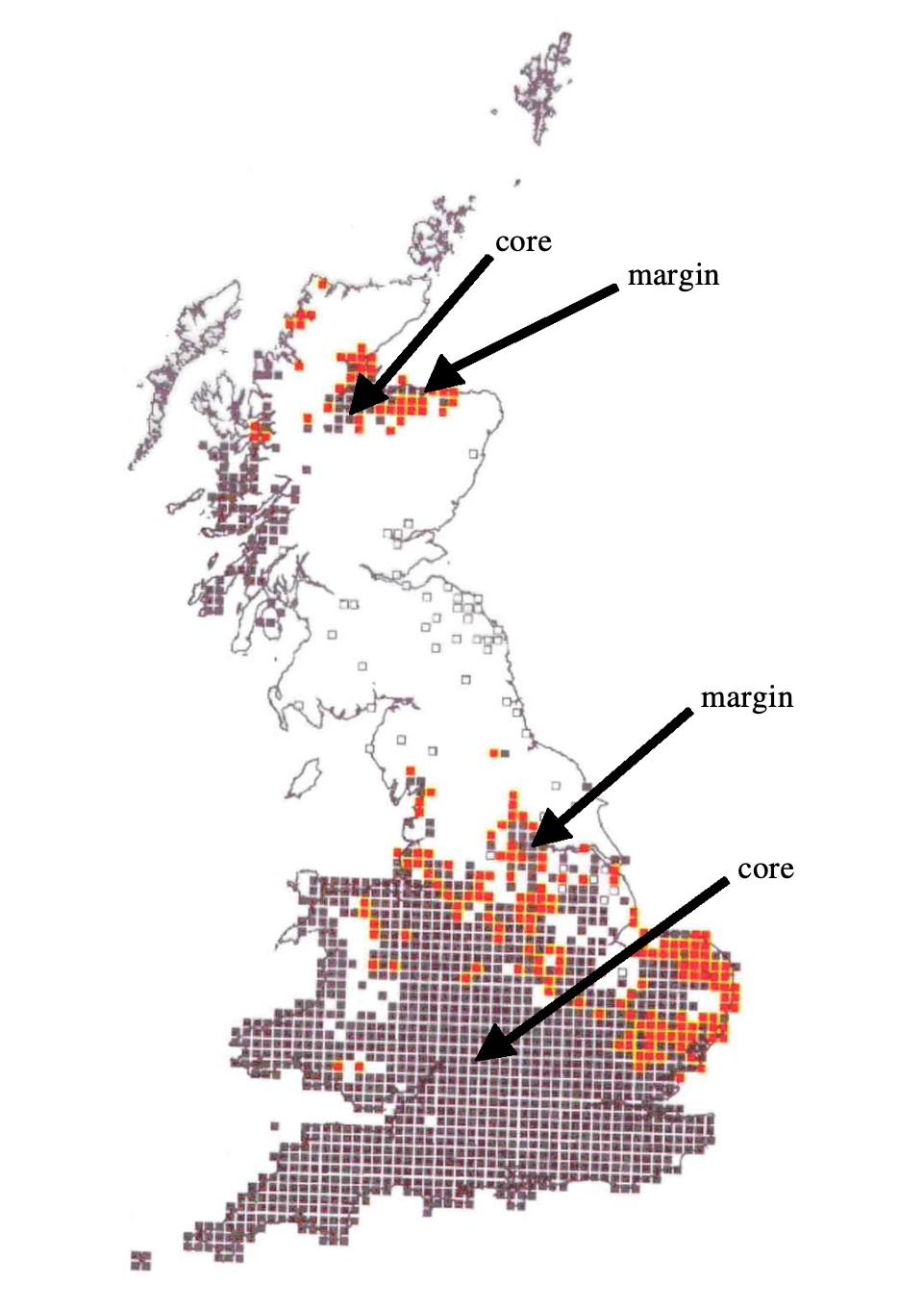

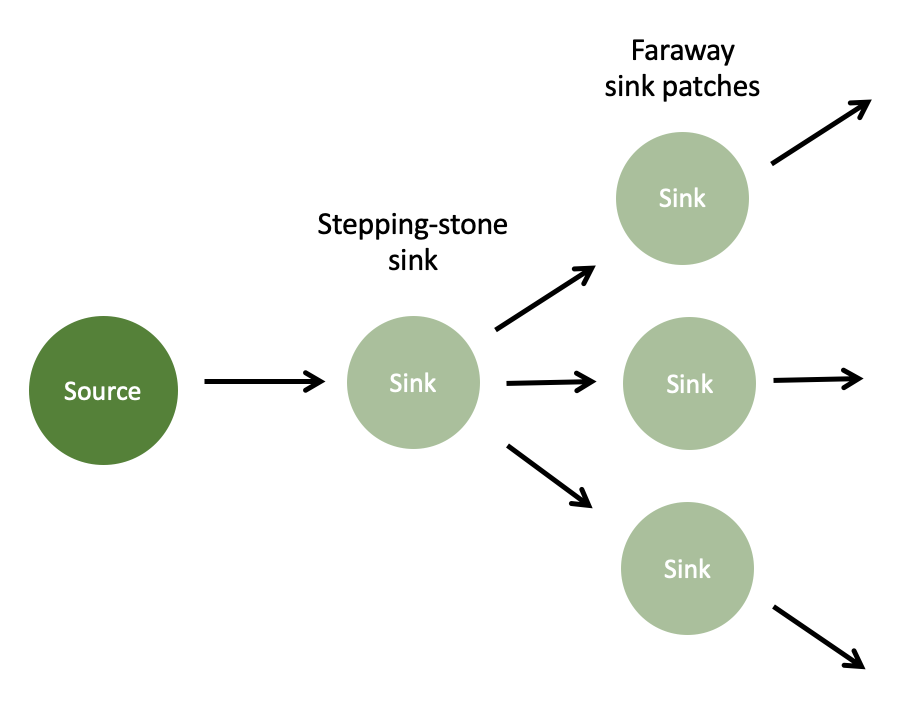

Understanding the mechanisms that limit species’ geographical ranges is one of the central challenges in biogeography theory. Historically, biogeographers have claimed that, at large spatial scales, climate exerts a dominant control over the distribution of biota, such that the broad outlines of the population are constrained by niche requirements. And as such, source-sink dynamics can be ignored as it typically operates at the species’ movement length scales.

Using a reaction-diffusion model that combines local growth and dispersal, we show that species may use sink patches near the bioclimatic limit as stepping stones to occupy faraway sink patches, thereby extending species distribution far beyond the climatic envelope. These stepping-stone dynamics may be substantial for species with high dispersal and low growth sensitivity—possibly even at large spatial scales.

For more, see my ESA (2020) talk and

Goel, Nikunj, and Timothy H. Keitt. “The mismatch between range and niche limits due to source-sink dynamics can be greater than species mean dispersal distance.” The American Naturalist 200:3, 448-455 (2022).

Distribution and resilience of savanna and forest

Climate change is expected to result in large-scale biome shifts. However, we lack a predictive understanding of which ecological processes govern biome distributions and whether biomes are resilient to global change.

We explore the interplay between fire-vegetation feedback and dispersal at the savanna-forest boundary using reaction-diffusion models, paleoecological data, and remote sensing products. We find that biome limits are determined by climate and continental-scale source-sink dynamics and dispersal barriers. Moreover, dispersal can generally allow biomes to recover after perturbations.

For more, see -

Goel, Nikunj, Vishwesha Guttal, Simon A. Levin, and A. Carla Staver. “Dispersal increases the resilience of tropical savanna and forest distributions.” The American Naturalist 195, no. 5 (2020) - 833-850.

Goel, Nikunj, Erik Scott Van Vleck, Julie C. Aleman, and A. Carla Staver. “Dispersal limitation and fire feedbacks maintain mesic savannas in Madagascar.” Ecology, 101(12):e03177 (2020).